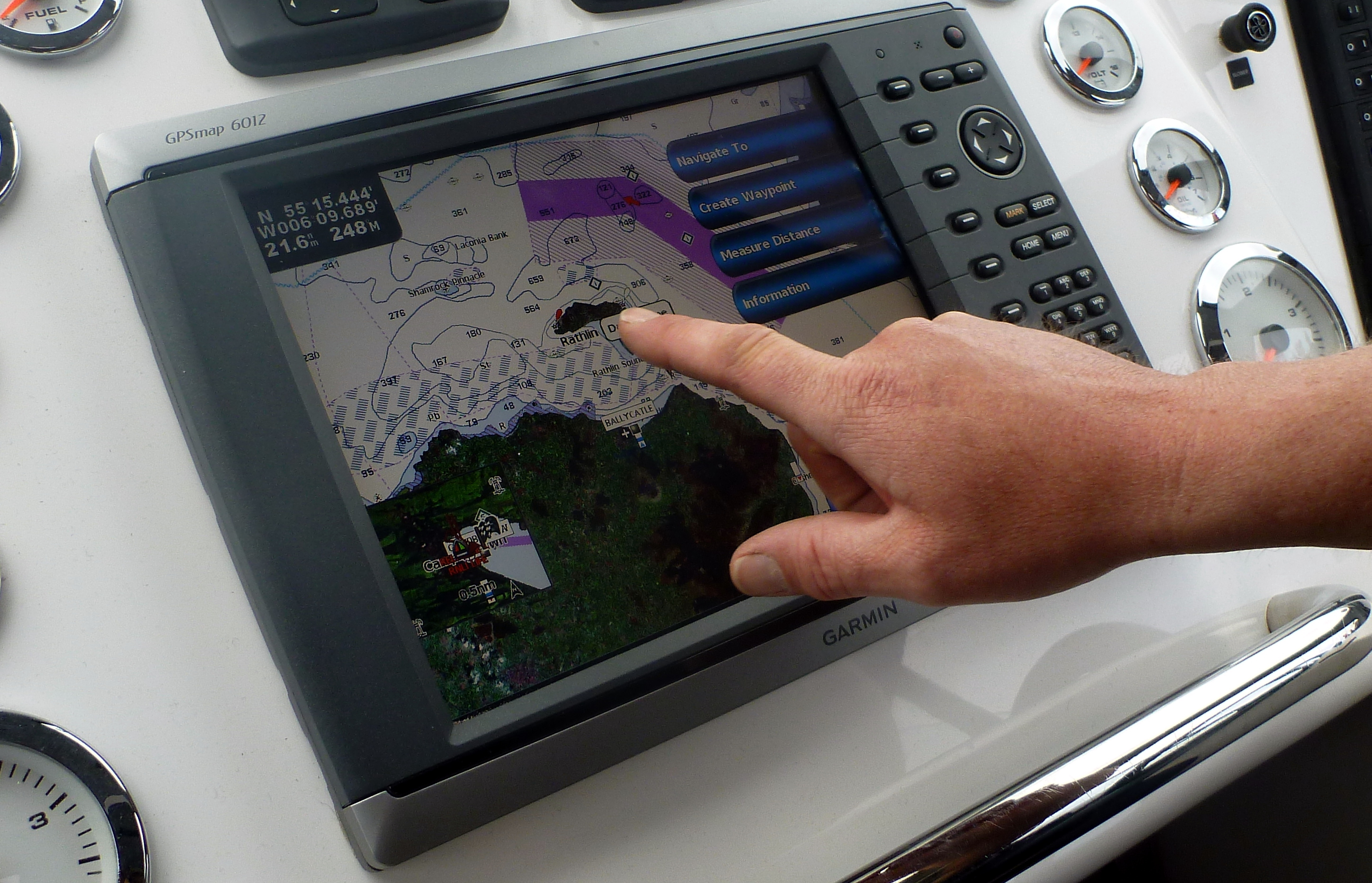

Askernish, South Uist, Scotland, May, 2007.

In 1889, a twenty-one-year-old Englishman named Frederick Rea was offered a job running a small school on South Uist, an island in the Outer Hebrides, more than fifty miles off the west coast of Scotland. He didn’t recall having applied for the position, and when he accepted it his relatives thought he’d lost his mind. South Uist was windswept, treeless, and only intermittently accessible, and it was seldom visited by anyone from the mainland except a few wealthy sportsmen, who came to hunt and fish.

South Uist, May, 2007.

Rea’s students were the children of crofters, or small tenant farmers, the island’s principal residents. The crofters subsisted mainly by growing potatoes and grain, raising starved-looking cattle and sheep, and gathering seaweed, which they used as fertilizer or sold. Most spoke only Gaelic. The children went barefoot year-round and often walked miles to school, even in snow, and on winter mornings each was expected to bring a chunk of peat for the schoolhouse hearth. The Scottish historian John Lorne Campbell wrote that South Uist in those days was so primitive that “the appearance of a pedal bicycle was sufficient to send the island’s horses and cattle careering in panic.” Yet Rea was captivated. He didn’t return to the mainland permanently until 1913, by which time his students had included two of his own children.

Rea’s schoolhouse stood near (and resembled) this old house. Garrynamonie, South Uist, December, 2008.

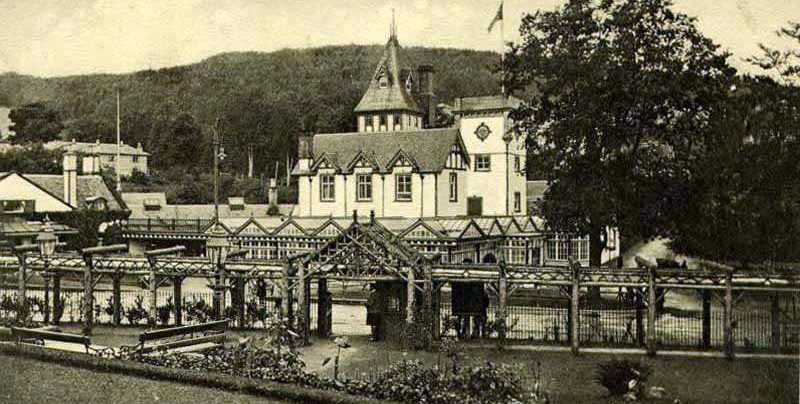

When Rea arrived, South Uist and several neighboring islands were owned by Lady Emily Eliza Steele Gordon Cathcart, a wealthy Scotswoman, who had inherited them from her first husband, who had inherited them from his father. She is said to have visited South Uist only once, but she made business investments, including the construction of hotels and commercial fishing piers. In 1891, probably hoping to make South Uist more attractive to wealthy tourists, she commissioned a golf course near a tiny farming settlement known as Askernish.

The evening view from one of the guestrooms at the Lochboisdale Hotel, which was commissioned by Lady Cathcart and opened in 1882. Lochboisdale, South Uist, December, 2008.

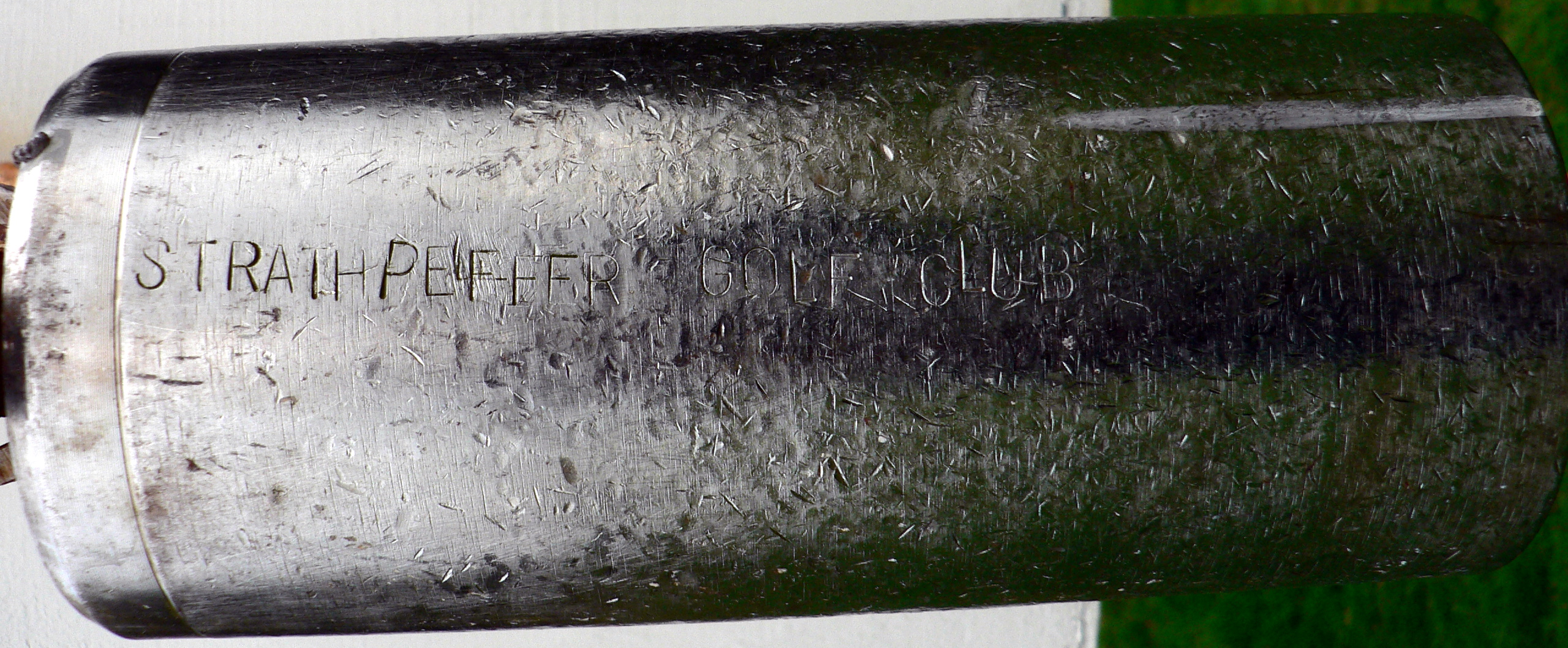

Rea, the schoolmaster, played the golf course with a friend when it was new, and he described the experience in his memoir, A School in South Uist, which was published in 1927 and is still highly readable. Lady Cathcart’s factor, or estate agent, Rea wrote, “told me that a professional golfer from St. Andrews had been to the island and had specially laid out an eighteen-hole course along the machair near his house, expressing the opinion that this part was a natural golf-link course.” Machair is the Gaelic word for “linksland”; it’s the root of Machrihanish, and it’s pronounced mocker, more or less, but with the two central consonants represented by what sounds like a clearing of the throat.

The machair of Askernish, May, 2007.

The factor invited Rea and a friend to play the new golf course one Saturday, and they met at his house. “Here we found quite a small party assembled,” Rea wrote; “beside his wife and children were a young lady cousin from Inverness, two or three clergymen and two junior clerks. Introductions over, we selected balls and clubs.” Rea didn’t say so, but the St. Andrews professional who had created the course was the most famous golfer of his day, Tom Morris, Sr., better known as Old Tom Morris.

The house of Lady Cathcart’s factor, mentioned by Frederick Rea in “A School in South Uist.” Old Tom Morris’s golf course began not far from its door. Rea’s friend dismissed golf, initially, as “a silly, stupid game,” but both men quickly became hooked. Askernish, May, 2007.

Lady Cathcart died in 1932. Her will included a provision for the perpetuation of the golf course. In 1936, a small airstrip was built near its northern end to accommodate wealthy tourists. (The passenger service was commercial but unscheduled; when a pickup was desired, the proprietor of a local hotel would send a homing pigeon to North Uist—the island still lacked telephones and, for that matter, electricity—and Scottish and Northern Airways would dispatch a plane.) Then the war came. The number of golfers dwindled. The course was reduced to twelve holes, then to nine, and the connection to Old Tom Morris devolved to legend. By 2000, what was left of the course was maintained by a small group of local diehards, who mowed the putting greens with a rusting gang mower, which they pulled behind a tractor.

Askernish , May, 2007.

I first visited South Uist on assignment for Golf Digest during the spring of 2007, and I visited it again in December of the following year, on assignment for The New Yorker. My New Yorker article about Askernish, called “The Ghost Course,” was published in 2009. Below are some more photographs I took during those two trips.

South Uist doesn’t have an airport. On my first trip, I flew from Inverness to Benbecula, one island to the north. It’s connected to South Uist by a causeway, as is the island of Eriskay, at the southern end. The only other passengers on my flight were two bank couriers, who were accompanying a load of cash, for ATMs. All the other seats were filled with “Bennetts Seat Converters” containing the day’s newspapers:

On my second visit, I took the car ferry from Oban. That trip took almost seven hours. We passed islands called Mull, Coll, Muck, Eig, Rum, Sanday, Sundray, Vatersay, Hellisay, Gighay, and Stack, among others. We also passed this lighthouse, on a tiny island called Eilean Musdile. It’s just off the shore of a larger island, called Lismore, which has a population of a hundred and forty-six. The lighthouse was built in 1833:

Most of the roads on South Uist are a single lane, and you share them with sheep. There are frequent bump-outs for yielding to oncoming traffic. Resident drivers become adept at gauging each other’s speed, and often slip past each other without seeming to slow down:

During my first visit to South Uist, I stayed at the Borrodale Hotel, about a mile and a half down the road from Askernish. The hotel’s laundry facility was just outside the door:

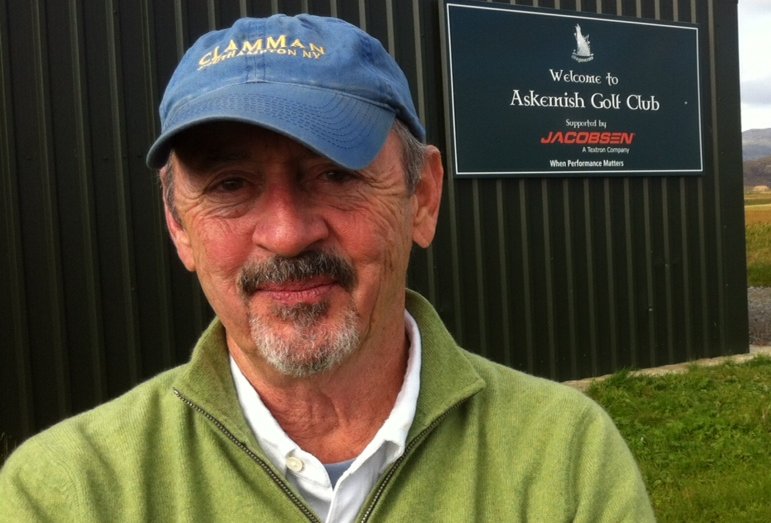

My guide to Askernish was Ralph Thompson, who was born on the mainland in 1955 and spent summers on South Uist, where his grandparents lived. One reason he liked those visits, he told me, was that he was allowed to go for weeks without bathing, because his grandparents’ house, like almost all the houses on the island at that time, had no running water.

His wife, Flora, was born on Barra, two islands to the south. Barra was even more isolated and primitive than South Uist, although today it has a small airport. Takeoffs and landings on Barra are scheduled to coincide with low tide, because the runway is a beach. Here’s one of the planes, which I photographed as it passed over Asknerish:

At the time of my first visit, Ralph Thompson was working with two links-course experts—Gordon Irvine, who is a turf consultant and a former greenkeeper, and Martin Ebert, who is a golf architect—in an effort to restore Old Tom Morris’s course at Askernish. In the photo below, Irvine is on the left and Ebert is on the right, and the flag in the background marks what they had decided was probably one of the original green locations:

I played all of the holes I could on that trip, and, with some of Ralph’s friends, helped test a few of the rediscovered ones:

We often had to play around cows and sheep, which grazed on the same stretch of linksland:

Even when there were no animals, the shot-making was challenging. This is a friend of Thompson’s:

When I returned to Askernish in 2008, the golf course had begun to look and play much more like a real golf course. The green in the photo below was puttable, and it had a single-strand barbed-wire fence surrounding it, to keep cattle and sheep from trampling it:

There isn’t much daylight in northern Scotland in December, but we had time for eighteen holes, and the weather was milder than the weather at home:

Since then, the golf course has come a very long way—as you’ll see if you visit the Askernish website. Someday, I’ll go back.

My most recent round at Askernish, December, 2008.